on escutcheons incorporated into the illustrations in books, to identify those who commissioned them

MS M.1166 (prayer book of Queen Claude of France), folios 6r, 15v, and 18v; collection of the Morgan Library and Museum; Tours, ca. 1517

Pages shown here roughly their original size (two by two and a quarter inches).

The site of the Victoria and Albert Museum has a print made in 1562 showing a printmaker engraving the copperplate for a heraldic bookplate.

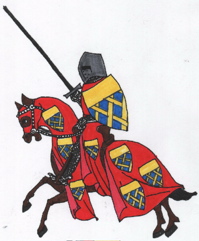

Both escutcheons and overall emblazons on caparisons are shown in the cited manuscripts and in others.

I already sketched some caparisons using my own arms, in creating sample completed versions of my heraldic display doodle sheets.

That's as close as I'm likely to get to making any, since I don't own a horse.

Cod. Pal. germ. 848 (the Manesse Codex), folios 231r and 166v; collection of the University Library Heidelberg; Zürich, 1305

BNF Français 2695, folio 57v; collection of the National Library of France; Provence, around 1460

BSB Cod.icon. 310 (Anton Tirol's armorial), folio 1ar; collection of the Bavarian State Library; southern Germany, between the end of the 15th century and 1540

BNF Français 2695, folio 57v; collection of the National Library of France; Provence, around 1460

I already sketched a trumpet drape using my own arms, in creating sample completed versions of my heraldic display doodle sheets.

I'm not ever likely to make a real one, since I don't employ trumpeters.

Cod. Pal. germ. 848 (the Manesse Codex), folios 42r and 166v; collection of the University Library Heidelberg; Zürich, 1305

Bodleian MS 264 folio 69r, (bas-de-page illustration); between 1338 and 1344, Flanders, Jehan de Grise and his workshop

BNF Français 2695, folio 57v; collection of the National Library of France; Provence, around 1460

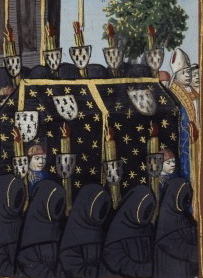

The owners of the arms appear to carry these banners themselves only when they are pictured alone. If they are accompanied, people in their service carry them.

I've collected all the banners from the Manesse Codex on a single page, as part of an article on heraldry in that book.

Photos of several are available on the Museum of London site. ID's 6914, 6870, 14162, 79.242/49, 79.242/50, 79.242/52, and A19910 each have a single painted escutcheon. ID A9517 has a row of three small escutcheons bearing different arms.

Museum of London ID 6916 has a single escutcheon in raised relief, as does museum number 1129-1892 on the Victoria and Albert Museum site.

There are photos of two heraldic tiles (accession numbers EC.24-1936 and EC.25-1936) on the Fitzwilliam Museum site, as well.

sections of a tile floor commissioned by Anne de Montmorency and created by Masséot Abaquesne in 1540, now in the Musée National de la Renaissance, in Écouen

earthenware pitcher from 15th-century Valencia, in the collection of the British Museum in London; Photo by Ursula Georges.

The Fitzwilliam Museum site has photos of heraldic maiolica pitchers from the 13th-14th century (including accession numbers C.29-1991, C.30-1991, C.31-1991, C.32-1991, C.47-1991, C.48-1991, C.78-1991, and C.57-1991), the 14th-15th century (accession number C.8-1904), the 15th century (accession number C.2165-1928), and the 16th century (accession number C.57-1927).

The Museum of London holds a heraldic jug from between 1266 and 1335, object ID# POM79[2048]<963>.

16th-century Iznik plate, in the collection of the British Museum in London; Photo by Urusla Georges.

The website of the U.S. National Gallery of Art has a slideshow featuring Italian Renaissance ceramics that includes photos of several maiolica plates featuring or incorporating heraldic escutcheons.

The Fitzwilliam Museum site has a photo of some 16th-century maiolica dishes with escutcheons at the center (accession numbers C.4-1961, EC.30-1938, C.79-1961, C.57-1927, C.38-1931 and C.81-1961), several painted with historic, legendary, or mythological scenes that have peripheral escutcheons (accession numbers C.10-1953, C.11-1953, MAR.C.61-1912, EC.23-1939, C.179-1991, C.86-1961, C.132-1933, C.133-1933, and C.180-1991) and one that has arms on a shield incorporated into a scene (accession number EC.19-1946). There are also one dish that has a scene painted on the bowl and an escutcheon surrounded by putti on the underside (accession number MAR.C.60-1912).

Several plates with escutcheons, including a couple that have pairs of them representing married couples, appear on the maiolica page in the Heilbrunn History of Art Timeline on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's website.

Sabine Bernard's page of photos of heraldic images from the Cloisters Museum in New York includes two photos of a 15th-century Spanish plate or platter with a large escutcheon in the center.

The Victoria and Albert museum website includes a mold-blown Venetian glass dish with an enameled escutcheon in the center (museum number 5490-1859). It might've been used for serving food or in combination with a ewer for washing hands.

The Mary's Maiolica Arts site has a photo of a plate in the Museum of London that has a central escutcheon and a scenic border. It gives a date of 1525.

The type of low-fire tin-glazed ceramic earthenware known as maiolica was produced in central Italy beginning in the 13th century. Heraldic motifs were popular from the beginning. The color pallette used in archaic maiolica (13th-14th c.) was limited to copper green and manganese brown, brownish-black, and/or purple. Additional pigments were adopted over time, and by the end of the 16th century maiolica designs were elaborate and multi-colored. It was common for available glaze colors to be substituted for heraldic tinctures not part of the pallette of a given time (green to be used where blue appeared in the arms, for instance), allowing armigers to have heraldic maiolica even if there weren't glazes that would render all the tinctures in their devices.

The term "proto-maiolica" is applied to Sicilian and southern Italian polychrome tin-glaze wares--a separate tradition from maiolica proper. Heraldic designs were common in that context as well, per page 458 of Barbara Ann Kipfer's Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology.

The Israel Museum proto-maiolica plate from 13th century with knight bearing a shield: accession #IAA 1998-3137

Plate with lots of pretty blue and yellow, 1250-1300, Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth

Sabine Bernard's page of photos of heraldic images from the Cloisters Museum in New York includes pictures of two15th-century Spanish bowls with escutcheons on the inside bottom, one that looks like it must be decorative and one that could be used for eating.

The Fitzwilliam Museum site has a photo of a deep maiolica bowl on a pedestal base from the first quarter of the 16th century that has an escutcheon in the bottom (accession number C.3-1932).

The Bildindex der Kunst und Architektur includes front, side, and top view photos of one that was made in Prague around 1352 and a single photo of one made around 1500, perhaps in Nürnberg, both from the collection of the German National Museum in Nürnberg

Karen Larsdatter has compiled annotated links to images of and information on medieval and Renaissance leather boxes, caskets, coffers, and cases.

Many leather cases were decorated not only with carving, stamping, and embossing but painting and guilding. It can be difficult to tell in black-and-white photos, but some were very colorful. The Réunion des Musées Nationaux in France has photos of a late-15th-century coffret from Italy and the Institut für Realienkunde des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit one of a 16th-century box from the Netherlands that are good examples.

W. H. St. John Hope's The Stall Plates of the Knights of the Order of the Garter 1348 – 1485 contains full-color facsimiles of 90 plates in St. George's Chapel in Windsor Castle. Photos of some of these and of later garter stall plates can be found in the Wikimedia Commons and various other online repositories.

(Additional images of the honor tree appear in folios 44r, 45v, 47v, 48v, 49v, 51r, 52r, and 52v. The arms hung on it vary from image to image.)

It's not entirely clear to me whether the shields on the tree from the manuscript at left are really honor shields made for the purpose or just the combatants' bucklers. Nowhere in the manuscript does anyone carrying a shield fight beneath a tree on which a shield showing the same arms is hung, and the shields on the tree might be simpler in shape than the ones the combatants carry because the ones on the tree are supposed to be honor shields or just because the artist took more time and worried more about detail when drawing the fighters. In any event, the manuscript does show that the concept of hanging small shields on trees at tournaments is a period one, even if it doesn't give any details.

The Lysts

at Castleton, which were held within the boundaries of my

home barony, used an honor tree (seen at right in

a

photo by Caelin on Andrede). Lord Thomas of Conway made me some

honor shields using the standards for that event. I painted the ones

depicted, with the arms of (from left to right) Áed Vilhiálmsson,

myself, Master Daniel de Lincoln, Vilhiálmr vetr.

The Lysts

at Castleton, which were held within the boundaries of my

home barony, used an honor tree (seen at right in

a

photo by Caelin on Andrede). Lord Thomas of Conway made me some

honor shields using the standards for that event. I painted the ones

depicted, with the arms of (from left to right) Áed Vilhiálmsson,

myself, Master Daniel de Lincoln, Vilhiálmr vetr.

I found online photos of S.C.A. "shield trees" from events held in the Kingdoms of Atlantia, The East, and Trimaris. (These are not particularly tree-like.)

I also found a couple of interesting photos of an actual tree hung with shields in the Royal Armories' main museum in Leeds (England).

There's was a photo of one (PID 2401) in the York Archaeological Trust Online Picture Library, but they seem to have removed almost everything from that resource, including that image.

The People's Collection Wales site hosts four photos of a 13th-century steelyard weight from Montgomery Castle bearing the arms of the Holy Roman Empire, England, Poitou, and the Earl of Cornwall.

The site of the Portable Antiquities Scheme includes photos of a number of medieval steelyard weights incised or embossed with heraldic escutcheons, including SOM-8DBE3C, SUR-23AE49, WILT-C4C051, and NMS-FB2526.

A steelyard is a type of scale, consisting of a long arm with an off-center pivot. The item to be weighed is hung from the shorter end of the arm, and a weight is slid along the longer end until balance is achieved. The position of the weight tells you how heavy the item is.

I'd guess the purposes of the markings on these weights are the same as those of the markings on coins. They'd indicate who's responsible for one (in the case of the weight, for making sure it is exactly as heavy as it should be) and make it harder for someone to counterfeit.

The site of the Victoria and Albert Museum has a photo of a sterling silver seal matrix from the late 16th century that bears the full heraldic achievement of Sir John Constable.

The site of the Portable Antiquities Scheme includes

photos of a great many medieval seal matrices, many of which feature

heraldic escutcheons as their central motifs. Here are a few

examples. (Details from photos made available through the scheme

under a

CC BY 4.0

license.)

There are also a

few more elaborate heraldic designs, like

SUR-486E0E,

which has three identical escutcheons in a radial pattern, and

LANCUM-1BD7C9,

which has an image of its owner holding aloft a shield with arms on it.

The site of the Victoria and Albert Museum has a photo of 16th-century covers for a bench cushion and a smaller pillow with escutcheons in their centers.

The site for the Victoria and Albert Museum has photos of 16th-century panels Maenan Hall, in Wales, and Windsor Castle.

The Peter de Dene window in the Cathedral and Metropolitical Church

of Saint Peter in York features several sets of arms. They are

royal arms, rather than the arms of private donors, but are good

illustrations of the style of heraldic stained glass from the early

14th century (Details from a photo by Jules & Jenny

available

on Wikimedia Commons under a

CC BY

2.0 license):

The site for the Victoria and Albert Museum has photos of heraldic glass panels from the 14th (museum numbers 6905-1860 and 6911-1860), 15th (C.9:1-1923, 81-1865, and C.289-1938), and 16th (C.63-1946, C.117-1924, 6819-1860, C.42-1919, and C.126-1929) centuries.

The Collection of Heraldic Stained Glass at Ronaele Manor, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania: the Residence of Mr. & Mrs. Fitz Eugene Dixon is available in its entirety in the Internet Archive and includes many color plates showing 15th and 16th century windows that were removed from buildings in England and installed in Ronaele Manor sometime before the book's publication in 1927.

The site for the Victoria and Albert Museum has a photo of a 15th-century chausible with the arms of the Duke of Warwick on the orpheys.

The site for the Victoria and Albert Museum has a photo of a panel from a villa in Prato, Italy dated to the middle of the 16th century.

The site for the Victoria and Albert Museum has a photo of a 15th-century display shield made of leather-lined wood on which the arms of the Villani family of Florence are shown.

The site for the Victoria and Albert Museum has a photo of such a purse from the mid-16th century.

I've read that purses had important symbolic roles to play in medieval weddings. I wonder if this purse, which records a series of marriages, might have been made for that specific purpose.

The online gallery of the British Museum includes a page from the Chronicle and Cartulary of Peterborough Abbey, dated 1325, on which two escutcheons appear, each next to the entry for one of those who held "feudal lands" belonging to the Abbey

BNF Français 5054, folios 244 and 248v; collection of the National Library of France; Paris, 1484

There are several photos of a panel from 1402 on the site for the Victoria and Albert Museum (museum number 414-1892)

There's one photo of an example from 1343 on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Accession Number 10.203.3).

There's an elaborately-decorated example in the Victoria and Albert Museum (museum number W.1-1958). It has a second, blank cartouche next to that carrying the arms of the duke who sponsored the workshop in which it was made. It is presumed that the recipient's arms would've been painted there.