I taught

a kids' tablet weaving class at the Barony of Bryn Gwlad's Candlemas

event in 2008. The kids were fascinated by the process, and produced

some very serviceable lengths of tablet weaving.

I taught

a kids' tablet weaving class at the Barony of Bryn Gwlad's Candlemas

event in 2008. The kids were fascinated by the process, and produced

some very serviceable lengths of tablet weaving.

I taught

a kids' tablet weaving class at the Barony of Bryn Gwlad's Candlemas

event in 2008. The kids were fascinated by the process, and produced

some very serviceable lengths of tablet weaving.

I taught

a kids' tablet weaving class at the Barony of Bryn Gwlad's Candlemas

event in 2008. The kids were fascinated by the process, and produced

some very serviceable lengths of tablet weaving.

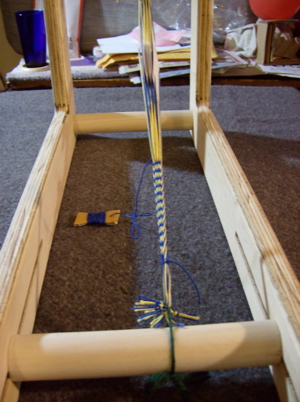

It is possible (and, in fact, not difficult) to tablet weave without any sort of frame or loom, but it's easier to keep tension even with one. Given that, plus the fact that I didn't know how old the kids I'd be working with would be (and thus how hard it would be for them to tension their bands themselves), I thought it best to use looms for the class. I considered a couple of simple designs, and settled on a "mini loom" designed by HL Toli the Curious. Lord Thomas of Conway (who lives in the barony) generously donated eight complete looms to me, for use in this class and future ones.

The looms are shaped like an upper-case letter "L". The shorter leg is a foot long and the longer a foot and a half. They are connected by three six-inch dowels, one of which the weaver can slide forward or back to adjust warp tension. They were quite convenient to transport and to use, and not at all intimidating to the kids or their parents (which I consider a plus). They are, however, completely modern in their design, and I was careful to mention that to the kids and to show them a sketch of the weaving frame found in the Oseberg burial so that they would know what the real thing looked like.

Since I wanted the kids to be able to produce something usable and attractive to them in a half hour , I chose to use size-10 mercerized cotton thread for this project. It's inexpensive, comes in a wide range of colors, and is thick enough to work up quickly and to make a reasonably wide band without a massive number of tablets. Each kid's warp required thirty-two pieces of thread (four for each of the eight tablets). I cut them about two and a half feet long, making a total of a almost 27 yards of thread per kid, equally divided between two colors. I think I made the wefts three yards long, bringing the yardage total per kid to 30. I made a point of telling the kids that real medieval tablet weaving was not done with cotton thread, but with wool, silk, and occassionally flax, with some metallic threads used for brocading.

The tablets I made myself out of 110# card stock. I created a printable sheet full of perfect tablet shapes and printed several copies. Then I cut out each individual shape with scissors, applied permanent adhesive to half of them using a Xyron Create-a-Sticker, and very carefully adhered them to the other half. Finally, I used a quarter-inch single hole punch to punch holes through both layers of card stock at once, using the printed circles as a positioning guide. It wasn't difficult, but it was tedious. I'd recommend finding a quicker way to work it, if you can. The finished tablets were an inch and a half across--pretty close to average for medieval tablets. I told the kids about the surviving medieval tablets that have been found and showed them life-size diagrams showing the dimensions of real medieval tablets from several different sites across Europe so they could compare them to the ones we were using. I also explained that while square tablets with four holes are most common in medieval contexts, tablets of other shapes and with other configurations of holes have been found, and showed them diagrams (not to scale) of a few examples.

I used paper shuttles, made by simply cutting some of the card stock trimmings from the tablets into rectangles, then slicing a curved piece out of each long side. They were modeled on one of the two thread-winders from the Viking Age I found on the website of the Museum of National Antiquities in Sweden (items number 28686 and 28687), images of which I showed the kids.

The shuttles worked fairly well, initially. I wrapped most of each weft around one, then twisted the last couple of inches into a loop, slipped it over the end of the shuttle, and pulled it snug. It stayed until the kids were ready for more weft--no problem. Unfortunately, they had trouble reproducing the loop, and if they didn't do it right and they dropped the shuttle, the weft all tended to unwind. After the class, my lord (who sat in on it) wanted to finish his project. He'd lost his shuttle, so I wound his weft around a bread tag, through the opening. It worked perfectly. The thread went on and came off easily when I wanted it to, but it didn't unwind itself when the tag was dropped. If I taught this class again, I would use bread tags as the shuttles for all the participants.

I considered

doing a circular warp on the looms, but decided it would be easier

to take the kids' projects off when they were finished if they

were just tied to two of the dowels. I determined to start each

length of weaving myself, for several reasons.

I considered

doing a circular warp on the looms, but decided it would be easier

to take the kids' projects off when they were finished if they

were just tied to two of the dowels. I determined to start each

length of weaving myself, for several reasons.

For each project I started by warping all eight tablets with the same two colors, matching colors on opposite corners. I tied all the threads through each card in a knot near one end. Then I ordered the pack so that the cards alternated in their threading (S-Z-S-Z). I tied a scrap of contrasting yarn around the threads near the knotted end, then around the moveable dowel. I gathered the other ends of the threads together, wrapped them around the upper dowel, and tied them on there.

Then I wove for a few inches, turning continuously forward a couple of dozen times, then reversing to eliminate the built-up twist. When I had enough of a strap woven to do so, I untied the threads from the upper dowel, slid my weaving down, and re-tied the ends around the upper dowel. Then I untied the scrap yarn, wrapped the end of the strap snugly around the lower dowel, and tied it on. I adjusted the moveable dowel if I needed to, to get the right tension. And I set that loom aside, ready for the class.

The pattern produced by this method is simple but striking. It's quick to emerge and easy to achieve, so it's perfect for small children.

But it also doesn't challenge one's creativity much. An older group would probably find producing more controlled patterns that require more thought and care much more satisfying. I recommend following the steps laid out in Shelagh Lewins' The Ancient Craft of Tablet Weaving: Getting Started to explore the way patterns are created in tablet weaving if your students are old enough for it.

In the class I taught, the kids used their fingers as beaters. It worked fairly well, but some of the very small ones found it uncomfortable after a while. If I were teaching this class again, I would probably get some craft sticks and sand them smooth, perhaps sanding unevenly to introduce a taper toward one long edge, and let them use those instead. They would resemble the Viking-Age beater described as "Strange Artifact 4" on the Arkeodok site (which has since been identified, though the website hasn't been updated) quite a bit. Of course, I showed the kids a picture of that beater in the original class, and would be even more careful to do so if the kids were using beaters that didn't look like anything from the period we were talking about.

Throughout the class, there were several completed tabletwoven bands on the table. I pointed them out to the kids at the beginning of the class, explained that items like those could be produced through tablet weaving, and assured them that if they were interested in tablet weaving they could with practice and more study make such things themselves. They represented different materials and different techniques and varied considerably in their complexity, the sort of designs they featured, their dimensions, and their colors. I borrowed them from a (much) more skilled weaver who lives in my barony.

I gave the kids who took home not-quite-finished projects a little handout to remind them of the most important points they needed to get to finish it.

I also had available handouts giving instructions for the construction of two different simple looms--the one we used and one that Master Herveus d'Ormonde (of White Wolf and the Phoenix) described on a tablet-weaving mailing list to which I belong. For those who showed a strong interest in continuing to tablet-weave when they got home, I had even prepared a few little booklets containing the text and illustrations from Shelagh Lewin's The Ancient Craft of Tablet-Weaving: Getting Started (produced with her kind permission). They cost a couple of dollars each to make (using a color photocopier), so I didn't hand them out to everybody, but if some kid were really enthusiastic and wanted to learn more, I wanted to be able to provide something she could sink her teeth into.

The event at which this class was held had a Viking-Age theme, and I therefore focussed on Viking-Age tablet weaving and tablet-weaving tools in my presentation to the kids. If you are interested in presenting information from later in period, you might offer manuscript illustrations like these showing tablet weavers instead of or in addition to information on the Oseberg weaving frame.

If you're teaching tablet weaving at a high-persona event or just want to use tools that look more like those used in period, you might be interested in the instructions for building a slot-together version of a weaving frame like the one from Oseberg and those seen in the illustrations above that Danr Bjornsson has uploaded to his website or the project diary for another break-down design on the Re-enactment Events site. (Or you might just rather know that White Wolf and Phoenix sell a complete peg-together weaving frame for US$45.)

Sword beaters (also known as weaving swords) and weaving daggers (which are really just short sword beaters) are also known from the Viking Age and through the Middle Ages (at least). I didn't have handy any photos of them when I did my class. But you might want to talk about them if you do one, especially if you use illustrations like those above that include them. There is information on a few from various places in James T. Lang's Viking-Age Decorated Wood: A Study of its Ornament and Style and Arthur MacGregor's Bone, Antler, Ivory & Horn: The Technology of Skeletal Materials. There are also a fair number of sites on the Web with information on reproductions, comments about sword beaters from various periods, etc. It's worth doing a good search if you're interested in learning more.

If you're looking for historically accurate tablets to use for weaving, Lynn the Weaver sells hardwood tablets for US$3 each and The Spanish Peacock carries rawhide tablets at 10 for US$8. Take care when shopping to verify what vendors mean by "wood tablets". Most of those who use those terms are really selling tablets made of very thin plywood.

If you're not worried about historical accuracy and you have more time for your class, you might consider making up a number of templates for weaving tablets and giving them to the kids along with some empty cereal boxes, scissors, and hole punches, and letting them make their own tablets on site. It won't take terribly long, it will show them that they can make more tablets for themselves when they need them (which might encourage them to try more tablet weaving on their own after the class is over), and it will spare you having to do all the cutting and punching yourself. Cereal-box cardboard is a good thickness for tablets, so you won't have to worry about gluing anything together.

This page was written and is maintained by Coblaith Muimnech, who owns the copyright to all elements not attributed to someone else, including all images less than 300 years old. Please do not reproduce any portion of it without express permission.

Click to visit Coblaith's homepage or the index to her articles on S.C.A. kids' activities.